Determined, diligent, dynamic women artists

Women artists seem to be all the rage these days. And rightly so.

The wealth of exhibitions and publications, the changing role of art galleries and museums, the expanding interests of private collectors, and the resulting attention of the action houses not only prove that there is a thirst for more knowledge but also that art history is a rather dynamic discipline.

Research on the role of women in the arts has accelerated in the last few decades. A proof of how much the topic has developed is that no longer someone would refer to Artemisia Gentileschi as the 'magnificent exception’. For several decades, Artemisia’s fame has put other women in the shadow but, in our slightly more informed times, we have an increasing awareness of the fact that there were other women who chose to work professionally in painting.

Still, Artemisia Gentileschi is still up there in her capacity of attracting a mainstream audience mostly because of the traumatic events of her young life. In recent years, she has become first an heroine of the #MeToo movement and then a protégé of fashion designer Victoria Beckam at the exhibition The Female Triumphant organised by Sotheby’s in 2019 in New York.

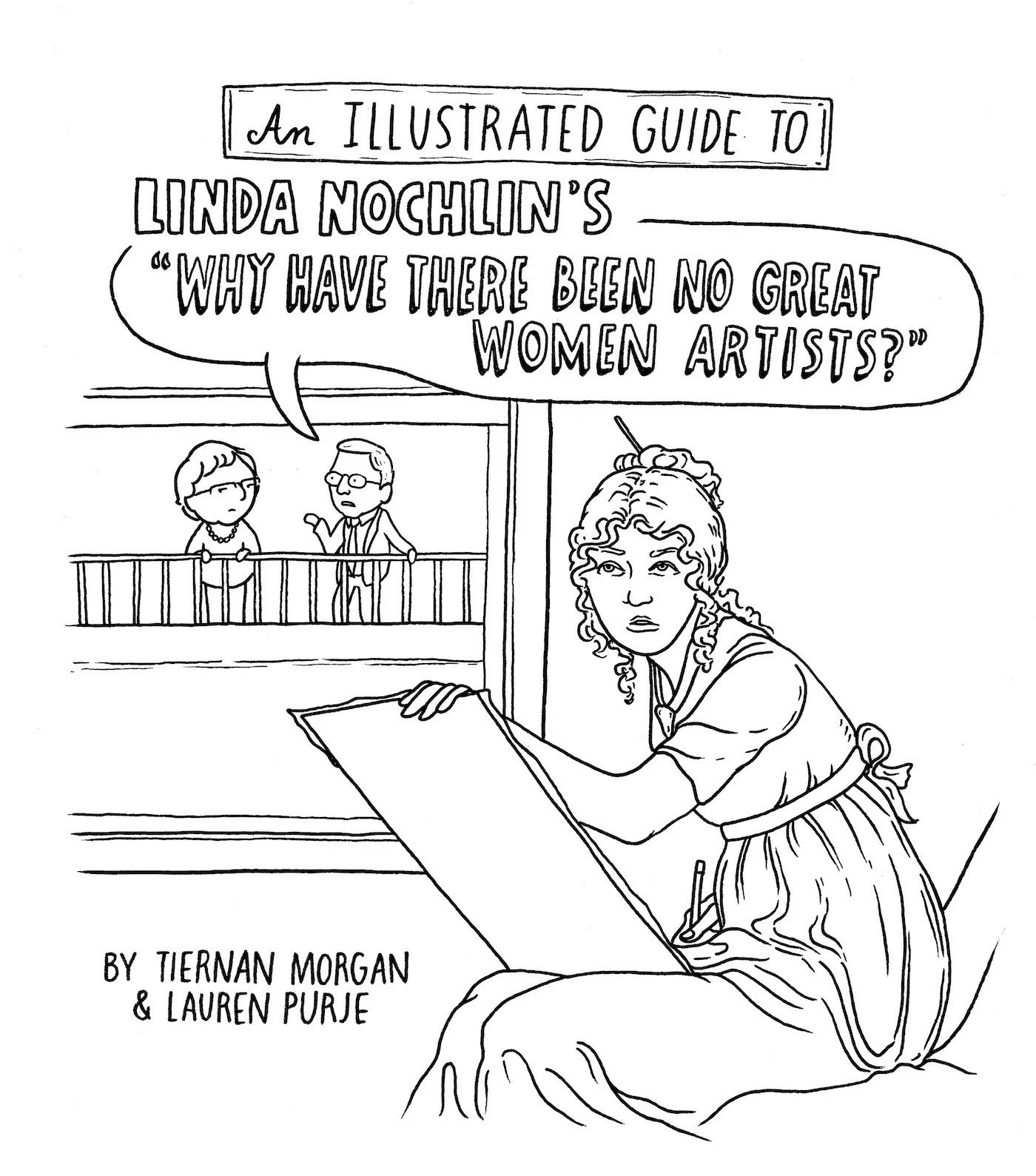

But a triumphant moment for all women artists had already arrived in 2017 when guests to Dior fashion show for Paris Fashion Week found on their seats a copy of Linda Nochlin’s Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? – an essay originally published in 1971 but still relevant for (not only feminist) writers, artists, and curators.

Also, the show was opened by a model wearing a T-shirt that read in all caps the provocative title of the essay which, at the hand of Maria Grazia Chiuri, Dior’s first ever woman creative director, became the slogan for Dior Spring Summer 2018 collection.

With a ‘does exactly what it says on tin’ subtitle – ‘Silly questions deserve long answers’, a line that was not reproduced in the reprints of the essay – the American feminist art historian reviewed the idea of ‘greatness’ and challenged the assumption that there weren’t great women artists.

There have always been creative women who have worked as artists throughout history. Unfortunately, their critical fortunes over the centuries have suffered from the tendency of several male critics to see women artists as ‘exceptional’, as opposed to ‘normal’, and read their works through the lens of biography.

One of the first and most influential examples of this tendency is Giorgio Vasari’s biography of Properzia de’ Rossi, a Bolognese sculptor who was active in the city during the first three decades of the sixteenth century.

Claiming that the marble relief of Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife for the Church of San Petronio would have been inspired by the artist’s unrequited desire for a young man, Vasari managed to overlook completely the main point – that a woman sculptor had received a public commission for the most important church in Bologna.

Portrait of Properzia de' Rossi in Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori, Florence, Giunti, 1568.

Although other women artists, such as Antonia, daughter of Paolo Uccello, were mentioned by Vasari in his 1550 edition of Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, et architettori (Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects), Properzia de’ Rossi was the only one considered worthy of a biography. Later, no less than six women artists made the 1568 edition of Vasaris’ compendium of artist biographies.

The ones Vasari chose to represent the three categories of women artists known at the time – professional artist, nun-artist, and aristocratic amateur – were Sofonisba Anguissola, Barbara Longhi, Diana Mantuana, Suor Plautilla Nelli, Lucrezia Quistelli, and Irene di Spilinbergo.

And six were also the women artists I selected for Women Painters in Early Modern Italy, a course I planned and designed last year. Of the Renaissance women artists discussed by Vasari the only one who made the cut is Sofonisba Anguissola.

Narrowing down the names was not easy. At long last, I decided to restrict the discussion to Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, Fede Galizia, Artemisia Gentileschi, Giovanna Garzoni, and Elisabetta Sirani, mostly because they are exemplary of the formidable obstacles almost all women artists had to overcome in order to practise painting professionally in a male-dominated art world. Although some patterns emerge in the recurring themes of education and upbringing, patronage and public, fate and critical fortune, they were diverse in their own personal experiences and production.

Whereas some art historians, feeling the need to over-correct centuries of male chauvinism in the history of art, write or talk only of women artists, I decided not to isolate women’s creativity from the historical canon.

I did not to omit men for double reasons. Firstly, as it has been pointed out already, this got women artists in trouble the first time round when, after the creation of the category of ‘woman artist’ during the nineteenth century, it was easier to omit it from the twentieth-century art history survey textbooks. And secondly, I very much agree with Linda Nochlin when, in her landmark essay, wrote “In every instance, women artists and writers would seem to be closer to other artists and writers of their own period and outlook than they are to each other.”

Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670), (after Albrecht Dürer) Lioness with an Open Eye, ca. 1639. Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome

Without falling into the temptation of focusing on the biographies of the selected women artists (even though sometime it served to bring artworks to life), the episodes of their lives that I discussed were the ones that could shed light on the context in which they lived and worked, the social expectations they surpassed, and the challenges they overcame.

The artworks too were situated in their historical and social context. Though idiosyncratic choices, the paintings I selected were the ones I believed most representative of a topic or an aspect of the women painters’ artistic production. With more works emerging on the art market and others being attributed or rejected, I tried to steer away from the controversial and contested ones.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1654 or later), Corisca and the Satyr, 1636-37. Private collection, Naples

Sofonisba Anguissola, like most Italian pittrici, specialised in portraiture but the close analysis of some portraits and self-portraits led to the identification of original features.

The investigation into Lavinia Fontana’s considerable accomplishments allowed for the exploration of other genres besides portraiture, while Fede Galizia’s recently rediscovered artworks were a means of demonstrating the necessary partnership between scholarship and art market.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s paintings served to illustrate the debate about the presence of a gendered twist and evaluate recent publications and exhibitions.

Giovanna Garzoni’s bequest offered the opportunity to discuss the role of the Academies just like Elisabetta Sirani’s graphic production to initiate a discussion on the role played by early writers and collectors.

Fede Galizia (1578-1630), Glass Tazza with Peaches, Jasmine Flowers, and Quinces, ca. 1607. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, QC, Canada

The information provided in the presentations came from multiple sources and is not my scientific studies or discoveries.

Each presentation was accompanied by a list of key sources (books, articles, and webpages) which I intend to update as the assessment of these artists continues to change.

For the six artists that were discussed in “Women Painters in Early Modern Italy”, there were dozens more.

Of too many it can still be said that we either just know them by name for whom any surviving work is known, or we think we know them as works have been misattributed.

Therefore, participants were encouraged to explore the topic further, close the gaps they saw fit, ask questions, and make comments.

Thank you for making it this far. If you're interested in collaborating on a project that combines art history with online education, I'd love to hear from you.